HISTORY

Life at Fort Wallace

First used in 1865, the Butterfield Overland Despatch (BOD) was touted as the best mail route from Atchison to Denver, Colorado by its owner. You could cross this great expanse of land for just $100. Stations were approximately 15 miles apart and were given different jobs. One station would be a “home” station that would feed the travelers while “cattle” stations provided hay and “swing” stations provided fresh mules and horses. The Smoky Hill Trail and the BOD greatly aided settlers in traveling over hostile Indian country. However, Indian raids became too frequent and there came a time when every wagon train had at least 22 wagons and 30 armed men. Many of the stage stops along the BOD route were connected to a fort for the safety and security that the military provided..

Wallace County had several BOD Stage Stops of its own. The most prominent, namely the Pond Creek Stage Station, was situated 1 1/2 miles west of present day Wallace. A “home” station renowned for its food, this little stage stop saw so many Indian attacks that Camp Pond Creek, a military encampment, was situated right next to it. When the BOD was sold to another company in 1866 (the Indian raids were so numerous by this time that the business had become unprofitable), Camp Pond Creek moved a few miles east to the Smoky Hill river and was renamed Fort Wallace in honor of W.H.L. Wallace, a general who died at the Battle of Shiloh.

Although Fort Wallace was no longer attached to the Butterfield Overland Despatch, soldiers stationed at Fort Wallace still had their hands full trying to protect those settlers who were moving through on their way west. Many of the most prominent trails that pioneers used cut straight through the best buffalo hunting grounds. Indians, whose livelihood depended on the buffalo, did not treat the trespassers lightly. Instead, as buffalo began to scatter and become scarce, Indians began to view their new neighbors with something less than friendly eyes. This made the presence of Fort Wallace an absolute necessity. Although according to official counts (details of the number of men in each Company and Division were recorded every month, you can see that count (here) the number of men stationed at the Fort never exceeded 350, these soldiers saw more encounters with Indians than any other Fort, rightfully earning Fort Wallace the distinction of being the “Fightin’est Fort in the West.” General George Armstrong Custer was stationed at Fort Wallace and saw his first battle with the Indians not far from the fort. Other great frontier men, such as George Forsyth, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Wild Bill Hickok, were also stationed at Fort Wallace at various times.

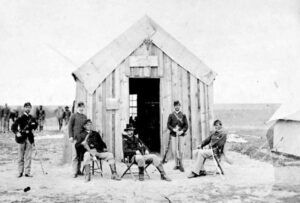

The majority of the buildings at Fort Wallace were made of native stone while the remaining buildings were wood. Eventually 40 buildings were constructed, enough to house and support four hundred men, even though the total number of troops topped 350 only a handful of times. Two Companies were usually enough to man the fort, but in October of 1871 14 Divisions (most of them Infantry) met at Fort Wallace. Despite the fact that Indian raids were constant and expected, for a period of 4 years the total number of troops stationed at Fort Wallace averaged just 75.

Despite the low population, the comfort level at Fort Wallace was not very high. Everyone had complaints about the food and soldiers spent a considerable portion of their pay to supplement their diets. With Fort Wallace being stationed so far from any major town, problems with the food deteriorating or rotting were rampant. Diseases such as dysentery and diarrhea killed many soldiers as did an outbreak of cholera in 1867.

In June 1867, Lt. Lyman Kidder and ten men from the 7th Cavalry of Fort Wallace started from Fort Sedgwick, Colorado with messages for Lt. Col. George Custer who was camped at the forks of the Republican River near where Benkelman, Nebraska is today. Custer had in the meantime left for Ft. Sedgwick, and Kidder (missing Custer’s trail) assumed that Custer had headed to Fort Wallace. When the Kidder party reached Beaver Creek in present day Sherman County on July 1, 1867, they were attacked by Indians and no one survived. Custer sent out a search party when he realized what had happened, and on July 11, ten days after the massacre, the search party discovered the murdered bodies of Kidder and his men. None could be readily identified except for the Indian scout.

The morning September 11, 1874 was another sad time in local history. One day’s journey east of Fort Wallace, the John German family, consisting of his wife and seven children, prepared to continue on their way west when they were attacked by a band of Cheyenne. Only the four youngest, all girls, were spared. After having just witnessed the brutal murders of their family, the four young children, Sophia, Catherine, Julia, and Adelaide were allowed to live. All four girls were taken captive by the Cheyenne. Due to the hard winter, however, the Cheyenne did not keep all the girls for long, and the two youngest, Julia and Adelaide (aged 7 and 5) were left on the prairie in what is now the Texas panhandle. They survived on their own for 6 weeks until they were finally found by soldiers. They were 7 and 5 years old respectively. Sophia and Catherine continued traveling with the Cheyenne, although they were eventually split up and traveled with different parties. Meanwhile, soldiers at Fort Wallace received word of the massacre and began the search for the remaining members of the German family, as well as negotiations with the Indians. On February 26, 1875, largely due to efforts made by soldiers stationed at Fort Wallace and elsewhere, the Cheyennes released Catherine and Sophia German at an Indian reservation. The two girls then traveled to Fort Leavenworth where they were reunited with their sisters Julia and Adelaide. (For more indepth information about the German Family Massacre, please read The Moccassin Speaks by Arlene Jauken or Girl Captives of the Cheyenne by Grace Meredith)